I'll start with Wylie and Trevor's questions, before they get away from me.

1) Wylie Elson asked me not long ago: "Why all the fuss about getting a studio? Why don't you just rent one?" The short answer is: money. We are on a fixed income, we can't legally work in Spain yet, and we ended up in a slightly expensive apartment in the Raval. There's not enough left over to rent a studio, never mind to start buying tools over here to outfit it with.

But the story gets more complicated and interesting, because it's almost certain that we will be leaving this apartment soon for various reasons. The #1 reason is that it's too expensive. The other #1 reason (tied for first place) is that Christina can not stand the Raval anymore (see Urban Filter below). She is dying to get out of this neighborhood (which will be a minor tragedy for me) and into a more tranquilo barrio, such as Gracia or Sants or somewhere near Montjuic. This adds another interlocked layer to the answer to Wylie's question, which is that because we don't really know where we will be living, and we want our workspace to be close to our flat, it's premature to rent a space. One of the big goals of our upcoming move is to lower our rent, so we will likely be able to carve off a bit of that fixed income in order to rent a studio.

This topic of getting a workspace also involves a cautionary tale about the dangers of expectations, and how they so often lead to disappointment. In the early months of this blog I talked quite a bit about our search for a workspace here in Barcelona. You might recall that this involved many visits to many different "collective" or "communal" workspaces. When we arrived in Spain and started talking to people about needing workspace, we were inundated with suggestions of specific "art-spaces" which worked on a collective level, and we were immediately seduced by the fantasy of big communal spaces with shared tools, as in the Bay Area's Crucible or American Steel, or even better yet, Tech Shop. Well, yes... it was a fantasy. It turns out there is no Tech Shop or Crucible or American Steel here, or anything even remotely like them. Yes, there are collective art spaces, but sculptors are not welcome due to "dust and noise" and of course there are no tools. We did find some halfway decent metal shops, but they are private. Shared metal-working tools in Barcelona? Ha ha, no sir. All of this took about 2 months to discover, which it to say it took two months for our fantasies and expectations to crash and burn.

The shipping container which lands in Berlin in 10 days which contains the Hand of Man also contains the rudimentary basics of a metal-working shop, so... fingers crossed that we can carve off some money and rent a space, once we find our new digs.

2) After reading my brief discussion of the Catalan independence movement, my brother Trevor asked about my personal stance on the matter. The short answer is: I don't believe I'm qualified to say. It's an immensely complicated topic, steeped in history and all the resentments that history and power engender, and I'm an American guy who has been here for 6 months. Also, I find that discussing politics is a quagmire I am almost always reluctant to enter, as there is always someone who will disagree with your position, opinions are almost never changed, and arguments (in addition to being frequent) are usually won by the more passionate and vociferous combatant, regardless of content.

Now, that being said, I can cautiously offer an opinion which may well change at any time in the future, pending new information, and which might piss off a reader or two (hey, don't be so sensitive! I'm an American guy who moved here six months ago!)

It seems to me that Cataluña would be better off remaining part of Spain, BUT... I think that if Madrid (which is to say the Spanish federal government) were to treat Cataluña more fairly, Catalans would be less prone to holding symbolic secession votes and being pissed off in general. I am familiar with only a very few examples of this unfair treatment, but here goes... (I'm sure that interested parties could read on this topic ad nauseum with a bit of Googling)

Cataluña is the most prosperous and industrialized region of Spain. My understanding is that it provides the highest per-capita flow of tax income to the federal government, and some even call it the economic engine of Spain. Apparently the only highways in Spain which collect tolls are in Cataluña, so Catalans are the only ones paying tolls in Spain, and yet the money all goes to Madrid. My understanding is that this is just one example of this sort of thing, and I think this kind of "special" treatment engenders resentment.

After the death of Franco, Madrid granted increasing autonomy to Cataluña, including the right to bring back the Catalan language which is now used in schools, government, and everywhere in between. That was a step in the right direction, and I believe that if Madrid would treat Catalans like the proud and accomplished people that they are, and stop taking advantage of them to subsidize the rest of the country, the people of Cataluña would be less inclined to splinter off. Cataluña, as an independent nation, would be extremely small and would lose the foreign relations and military resources (as well as others) afforded by being part of Spain.

Just my opinion.

• The Urban Filter is nothing more than a name I have devised for whatever psychological mechanism I have in place which allows me to selectively filter out negative experiences in the urban environment. Christina doesn't have this filter, or at least hers is less well developed; hence her difficulties with the dense and bizarre neighborhood we live in.

I talked a few months ago about how some people need to shield themselves from the onslaught of human energy in urban spaces with the use of things like sunglasses, headphones, and hoodies. I have found that I personally do not need these devices; I have a built-in protection device, an urban filter, which allows me to look past the homeless and the junkies and the groups of tourists. I can actually adjust my filter on the fly and choose to essentially ignore people altogether if it suits my mood.

On our recent trip to Venice we had a conversation on this topic with our friends Jamie Henthorn and Ash, discovering in the process that one of them (Jamie) was more discerning/oblivious like me, and the other (Ash) was more like Christina. Jamie provided the insight that Ash is simply in possession of (or afflicted by) a developed empathy instinct which made her feel all the pain of all the damaged people in the city, thereby transforming a walk down a city street into a harrowing experience. This insight suddenly put Christina's difficulties in the Raval into a new light.

She feels the pain of the city's broken people; I don't.

I can filter all of that out and soak up the energy of the city (which, if I am honest about it, really means soaking up the energy of the people... primarily the happy, the young, the lovers, the ones who are present and engaged.)

Ironically, I have come to love the Raval. Sometimes I leave my sculpture class late in the evening, and I ride my bike up through the Rambla de Raval. That ride, in the twilight, through the laughing people and the crying people and the street markets and the trees and the cars and bikes and tourists is magic. It sounds corny but it's like the tapestry of humanity is laid out before you and all you have to do is move through it. You are a part of it.

• Damien Hirst / Italy. Our trip to Venice continues to reverberate for me. In retrospect it was a great trip and it was much more than a great trip; I find myself thinking often about Venice and about the art we saw there, especially Damien Hirst's work.

To be honest I am struggling with my newfound interest in Hirst; he is a distasteful character in so many ways and yet a compelling and fascinating one. Like so much in life there are reasons to like him and reasons to dislike him, but what might be a bigger tribute to him than my thoughts about any individual artwork is the fact that my feelings about him are elevated past like and dislike to something like love and hate.

I think that his approach to art is, in the end, as much a part of what makes him interesting as the art itself. It should be noted that certain elements of his approach, such as his use of paid craftsmen to execute the work, have certainly not been pioneered by him (Jeff Koons comes to mind, but I despise Koons' work so thoroughly that I can't be bothered to learn enough about him to use him as a case study). As stated in the last post, as a craftsman I have a hard time with this one while simultaneously admiring it. Hirst himself makes the case that he is no different in this regard than an architect, who of course brings the idea and design but does none of the execution, and subsequently receives the credit and fame (typically without any controversy). It occurs to me that movie directors almost fall into the same category.

This topic has caused me to tentatively begin to investigate my own relationship to craftsmanship and authorship. What would it be like, I wonder, to put out into the world an artwork which I had directed, as if in the role of an architect, but which I had had no role in fabricating? Conversely, what are the benefits of actually being the craftsman? How, if at all, do these relationships change if an artist gets partial help in constructing a piece? (When I constructed the Subjugator in 1996 I did all the work myself, with the exception of the radio-control interface board, which was designed and built by my friend Mike Fogarty. I have always been quick to give credit where credit was due... but what if that RC board was a store-bought product instead of something made by a friend? Surely in that case I would feel no need to mention it. Does any of this diminish my "authorship" of the Subjugator?) I do gain important rewards from constructing my own work, such as a sense of pride and a sense of accomplishment. And each newly constructed work adds to my knowledge base in such a way as to enable further "reach" in future pieces. I have become a walking database of technical knowledge, and I wonder if someone in Hirst's position feels that way... or has any regrets about the degree to which he does not feel that way. On the other hand, as I mentioned in my last post... imagine how much work one could "make" if thinking up the concept was the only job. Making good work takes time, and this of course slows down the process. Ideas come faster than work can be made, usually. A common criticism leveled at Hirst is that it's harder to fabricate good work than it is to think of the idea. I'm not so sure I agree. Art succeeds or fails on it's underlying idea, and coming up with an idea that can stand the test of time is no small task. Hirst of course has the funds available to make those ideas into substance, which differentiates him from most of us who have good ideas which never go anywhere.

Another way in which Hirst secures the mantle of "controversial" is his apparently voracious appetite for stealing other people's ideas for his own work. This is something I am less ambivalent about, but even still I see many sides of the issue. Ironically, I have previously within this blog stated that I very much liked the book "Steal Like An Artist" by Austin Kleon. Kleon makes the point that everyone steals, and it's a valuable technique for getting into the practice of art-making, but his ultimate message is more about using appropriation as a way to find a path to your own unique voice. I do not yet have enough knowledge about the trajectory of Hirst's career to understand if he did just this, although initial readings of his propensity for appropriation over quite a long span of time do suggest that he has less qualms about nabbing other people's ideas than what might be considered "normal." My take on the page linked above is that Hirst's standard MO is to re-work a piece just past the 10% threshold for avoiding copyright infringement (which turns out to be a myth anyway) and then give it a much better name, often involving cosmic or cryptic language. And although it's hard to see this as anything other than despicable, maybe it's more complicated than that. In leveraging his fame and his name, hasn't Hirst brought an artistically valuable idea into much broader view than it otherwise would have been? Hasn't he also in fact elevated the name and the fame of the artist from whom he "borrowed?" The fact that he does it all in the service of his own financial gain and aggrandizement certainly falls on the "despicable" side of the spectrum, but I doubt there's any way he could "give credit where credit is due" and come out undamaged. It's certainly a clear demonstration of the power of a name.

In contrast to Koons, about whose work I couldn't care less, Hirst's work variously inspires in me love as well as hate, or at least indifference. To me, his "Spot Paintings" are horrible.

Not so much because they are horrible paintings, but because they are both stupid / pointless AND pawned off as some sort of genius by dint of the fact that they came from Hirst himself (who, unsurprisingly, paints almost none of them). It's as if he was experiencing a lull in his flow of ideas but felt he needed to keep putting out work, and devised these paintings to fill the gap, almost daring anyone to call them out for the crap that they are. In fact I think these constitute a sort of "abuse of power." I feel similar derision for the "Spin Paintings."

On the other hand, I find most of his work which touches on death to be fairly compelling. I think works such as "A Thousand Years" and "Mother and Child Divided" are at least thought-provoking (which is actually saying something) if not actually great. Apparently Francis Bacon, who I LOVE LOVE LOVE, had a strongly positive reaction to A Thousand Years.

As I discussed at length in my last post, I very much liked Hirst's work on display in Venice. But my favorite works of his right now are those which blend beauty and death, such as his "portrait" of Kate Moss

And even more so the sculptures "Virgin Mother"

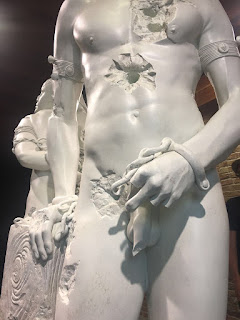

and "Anatomy of an Angel"

I love these pieces for the impact they deliver, the messages about the power of beauty and also its frailty and ephemeral nature, the presence of musculature and blood (and by extension, death) which is ever-present beneath the skin, and in the case of the last one, the secular message of exposing the human anatomy of an angel. It's as if he found a way to "hide" an anti-religious sentiment in a sculpture which, by its form and material, otherwise does a pretty good job as coming off as religious.

Clearly, I'm currently intrigued by Hirst. Another reverberation of our trip to Venice is a current interest in Italy itself. I don't have so much to say about that, other than that I am hoping to be able to operate the Hand of Man for Maker Faire in Rome in December (there is currently no actual reason to be optimistic about this... it's just something I hope I can arrange), and hoping to take a two-week marble sculpting workshop in Carrara (home of the world's most famous quarries of white marble) in August. That is something which I quite likely will actually be able to do, and boy am I excited at the prospect.

Also, everyone should listen to Laibach's re-working of the Italian National Anthem from their amazing album Volk. (European readers might need to use a VPN to get that video to load)

I promise to do another post soon, with photos of my ongoing sculpture work. The photos are actually ready to show, but it doesn't seem right to bury them at the bottom of this sprawling post. Soon, I promise.

OK, lastly, am I the only one to notice the similarity between Javier Bardem's character in the new Pirates of the Caribbean movie and Till Lindemann?

¡Hasta pronto!